The Complete Guide to Preparing for Service

How to improve fertility and financial returns during the service phase

In basic terms, all suckler herds are reliant on cows getting pregnant quickly and easily, producing and rearing a calf and returning to service again. But there’s a lot that influences the success of the service period, so we look at how precision service can maximise herd health, fertility and profitability.

To help you navigate this blog, we’ve created some useful links that will take you directly to the section that you want to read:

1. Be clear on your service objectives

2. Understand the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) worth tracking

3. Review last season’s performance

5. Managing cows/bulls effectively

Pre-service preparation

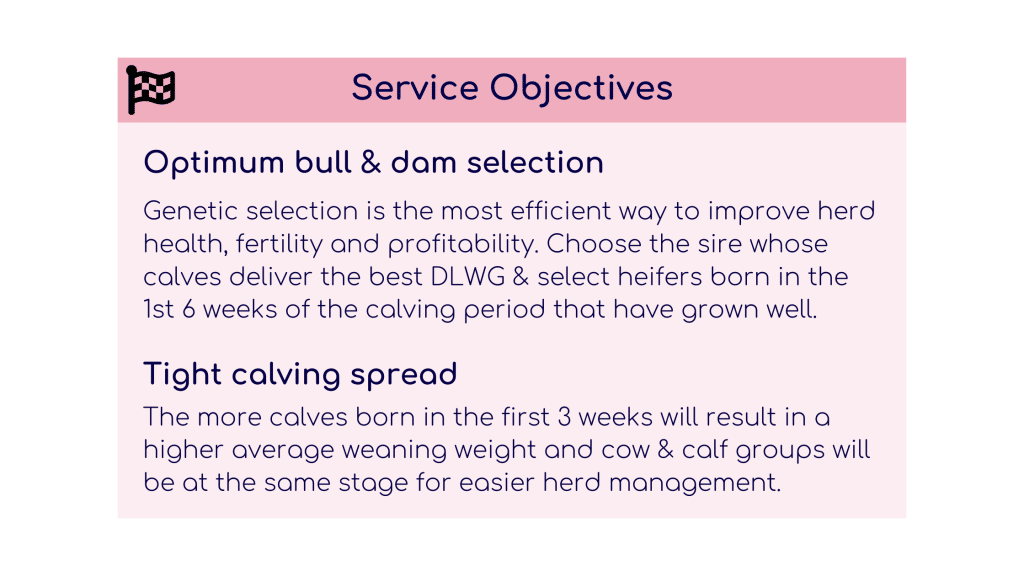

1. Be clear on your service objectives

The objective of any commercial suckler herd is to be healthy, productive and profitable, says AHDB knowledge exchange manager, Emma Steele. “Genetics are the foundation of the herd – but without good management you can’t achieve your objectives.”

Combined, optimum genetic selection and tight calving spread are the most efficient ways to improve herd health, fertility and profitability. ““Carefully plan genetic selection and work back from what you want offspring and your system to achieve,” she says. “You want cows to be as close to a 365-day calving interval as possible.”

Aim to calve down as many as possible in the first three weeks of the calving period to achieve higher average weaning weights and easier management of cow and calf groups. “You want to have 65% calved in the first three weeks of the calving window and 80% by six weeks.”

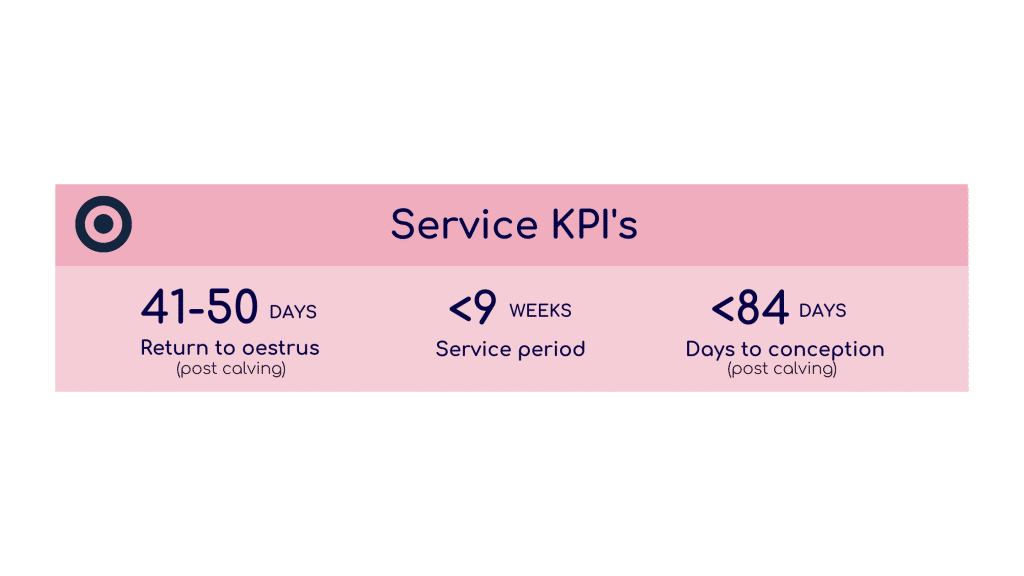

2. Understand the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) worth tracking

Service KPIs are the measurable goals that relate to your service objectives and it pays to keep track of them.

Suckler herds differ from dairy herds in terms of service KPIs, says Ms Steele. The two main service KPIs are calving interval and service period. “The average gestation period is 280-290 days which means cows need to get in-calf within 80 days of calving to achieve a 365-day calving interval,” she says.

Aim for a service period of <9 weeks. “A service period of nine weeks will help keep a tight calving period of <12 weeks,” she says. “Heifers should have a shorter service period of six to eight weeks and be at the front of the calving block; this gives them more time to recover after the first calf and successfully rebreed.”

First-time calvers will take longer to recover from calving and subsequently to get back in-calf; keep them at the front of the block to maintain a tight calving period.

3. Review last season’s performance

Data is a powerful tool and, when combined with observations, reviewing both herd and individual performance can inform breeding decisions.

Set out your breeding goals: What do you want to achieve as a business? “Are you looking to breed replacements, store cattle or finished stock,” says Ms Steele. “How you review and value performance is determined by what you were and are aiming to achieve.”

Consider:

- Will your breeding goals improve business profitability?

- What KPIs are you striving to achieve to reach your goals?

Having a log of breeding activities enables you to benchmark and compare data from previous seasons.

Consider:

- What KPIs from previous seasons have not been met?

- Where did losses and challenges occur? Conception? Calving? Weaning?

- Can breeding decisions help overcome the challenges?

- What can be done to improve KPI performance?

- Is it time to introduce new genetics into the herd with the use of AI?

When reviewing performance, look at both your own records and breeding data like estimated breeding values (EBVs) and indexes, advises Ms Steele. “Commercial suckler cows tend not to have EBVs so keeping activity records on service and calving activity can give you insight year-on-year,” she says.

“An animal might look good genetically – but if your management is good and they are, for example, falling outside of the nine-week service period or needing excessive intervention then you need to be asking if they should be kept in the herd.”

Aim to have 90% of cows calving within 370 days of their last calf, she adds. If they are not, ask why. “Is it because of condition – are they receiving adequate nutrition? Is the calving period excessive, or is there a health issue?”

Reviewing the bull’s performance and comparing against his EBVs will highlight if he’s performing to his potential and producing offspring that meet your breeding goals.

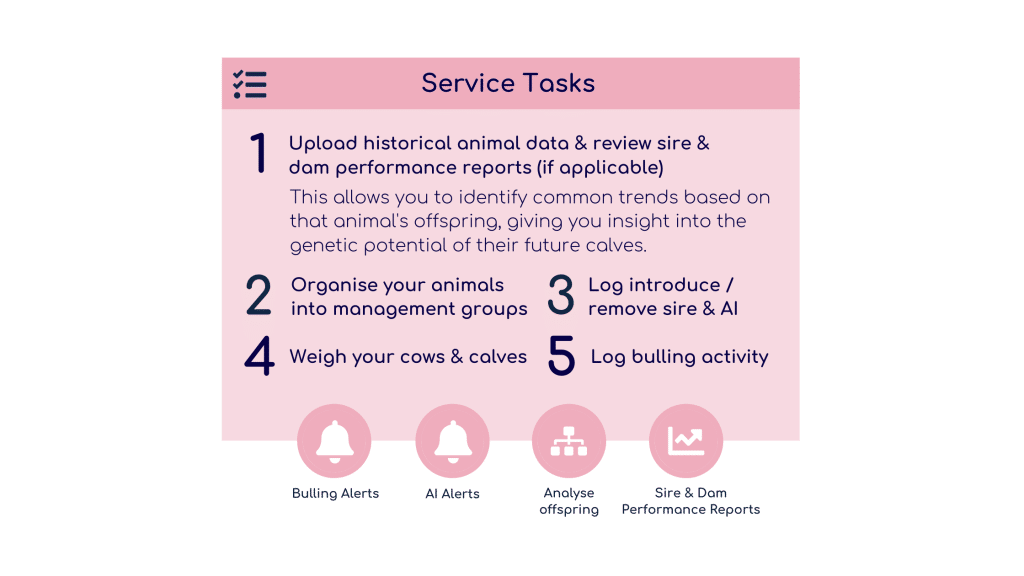

You can use Breedr’s KPI report tool to compare 33 breeding KPIs from previous seasons. Using the dam offspring performance report – to sort animals based on desired KPIs and traits – allows you to clearly mark cows for breeding or culling.

And even if you’re new to Breedr this tool is still available; simply import your historic breeding data into your account – you don’t have to wait to begin analysing data.

4. Selecting what to breed

Genetics play a vital role in the success of a suckler herd: Maximise your herd and business potential by carefully planning what to breed from. It’s useful to keep notes on every animal but key times are at scanning, calving and weaning: If she’s barren, lost the calf, or had problems from calving to weaning, should she be culled?

Cows

Whether you’re breeding for replacements or beef, when selecting cows consider the below traits alongside performance/KPI reviews:

- Cow size; moderate size animals cost less to maintain and have a greater chance of weaning at 45% of their mature weight. A recent study suggested the optimum weight is around 680kg.

- Which cows calved unassisted and with ease

- Which cows weaned at >45% of their mature bodyweight

- Which cows have the best conformation and maternal traits; feet, udders, milkiness

- Which cows have a good temperament

“Efficient cows with good milk production have calves that wean at >45% of their dam’s mature bodyweight – good daily liveweight gains are essential if offspring are to hit beef/breeding KPIs,” says Ms Steele.

“And there have been links found between temperament and productivity; highly strung cows are not only a safety risk but also tend to have poorer fertility and lighter calf weaning weights.”

Use the dam performance report in the Breedr app to review offspring’s DLWG performance. The report also lets you rank dams in performance order for service, pregnancy diagnosis (PD), calving and weaning KPIs.

You can also review individual dams’ calving history using the offspring tab – accessible through the web app – which will show you traits like calving ease and calf vigour.

Heifers

Fertility is a key driver of suckler herd profitability and therefore it is vital that heifers selected for breeding have developed enough to be bred and calve down at two years old.

To achieve this, heifers need to be no more than 15 months old at first service – but maturity is of equal importance. Genetics play a role in age at puberty, but nutrition has the greatest impact, with health status also an important consideration.

Setting weight targets and implementing rigorous visual and genetic selection will ensure only the most productive heifers enter the herd. “Heifers need to weigh 65% of their target mature bodyweight at first service,” says Ms Steele. “To achieve that she needs to be hitting a DLWG of 1kg/day suckling from the cow and 0.7kg/day once weaned.”

Using the estimated growth model within the Breedr app can help you predict future weights and track if heifers are under or overachieving target weights.

“It will cost you an additional £600/heifer if you calve at three years old – so it stacks up economically to make sure you have the management in place to produce young, fit heifers that hit development and breeding targets.”

Ms Steele advises only breeding from heifers that were born in the first six weeks of calving as these will be the most fertile animals and keep the calving period tight. “If you begin selecting heifers at birth, use a coloured tag system to mark them as potential replacements or non-breeders; it will make selection at weaning quicker and easier,” she says.

“At weaning, heifers can then be selected on birth-to-weaning growth rate. “It’s a good indicator of the dam’s milkiness and the heifer’s genetic potential; also consider soundness of leg and foot – and that of the parents,” she adds. “And as with cows consider temperament.”

Pre-mating checks

Dr Joe Henry, farm vet at Black Sheep Farm Health in Northumberland, advises that pre-mating checks carried out by a vet will help with breeding management and save you money.

“Reproductive tract scoring will tell you if they have a functioning reproductive tract and if they are cycling. Pelvic measuring will tell you if they are physically capable of birthing a calf,” he explains. “You don’t want your bull expending energy on a heifer that isn’t going to get in-calf or does but ends up having a difficult calving.”

Herds that are served by AI will almost always have these two pre-mating checks; whether you’re serving artificially or using natural service it is a worthwhile investment, he says. “Plan ahead, you want to be carrying out these checks 2-3 weeks before service dates.”.

Bulls

The fastest way to make genetic progress is through effective bull selection; a combination of visual and EBV assessment and selection indices that complement your breeding and business objectives.

For breeding your own replacements consider maternal EBVs, particularly direct calving ease. For selling calves as stores consider daily liveweight gains, and for finishing cattle consider growth and carcass traits, advises Ms Steele. “If you have two bulls with similar EBVs select the bull with highest accuracy.”

Example EBV considerations:

- Herd wanting to breed own replacements; experiencing difficult calvings and concerned about oversized cows = Look at direct and maternal/daughter calving ease and mature cow weight.

- Herd wanting to use a terminal cross; sells stock deadweight and wants to focus on carcass and meat quality = Look at eye muscle area, fat depth and carcass weight.

- Herd selling store cattle as yearlings; focus on market return = Look at 200 and 400-day weight, as well as body condition score.

If you’ve only got one bull on-site and want to breed both replacements and fat stock, they need to have a balance of maternal and terminal EBVs. “You want your bull to have above average terminal traits and maternal/ self-replacing indices.”

A lot can be gained by looking at a bull’s offspring: You can use the Breedr app to review offspring performance like DLWG, with calving ease and calf vigour traits available from the web app.

“If you are purchasing bulls then buy from a trusted breeder who has similar breeding goals to you,” says Ms Steele.

Claire Brooks, lead farm vet at West Ridge Vets in Devon, says the best time to select bulls is three months in advance of work – especially when purchasing them. “You want to have plenty of time to prepare them for work,” she says.

“You don’t want to be making drastic changes to diet or administering medicines and vaccinations close to service – they are very sensitive to change which can result in lower production and less functional sperm.”

Bull fertility checks

One in four bulls is sub-fertile, says Dr Henry. “So it’s really important to make sure your bull is in full working order with a pre-breeding examination a good two months before the service period.”

Checks include:

- Full physical from head to tail

- All aspects of the reproductive organs

- Semen quality

“Undertaking these checks will help you identify bulls with lower functional sperm as well as physical issues like lameness that may prevent them from mating,” says Mrs Brooks. “Getting it done in advance will give you time to make changes and for sperm production to recover, which can take 8-12 weeks post illness, lameness or nutritional challenge.”

Buying in replacements for breeding

For some farms the most practical and/or economical option is to buy in replacement stock – but there are risks associated with this practice.

Replacements might be bought in when:

- You have a bull with more terminal traits than maternal

- You want to change breed

- You want to introduce new bloodlines

- You want to instigate immediate change

“Herds can speed up the process of obtaining particular traits by buying in replacements,” says Ms Steele. “But there are caveats.”

Safeguarding the health status of your herd is paramount, says Mrs Brooks. “Bringing infectious disease onto your farm is disastrous; it can take years to eradicate from your herd – or even to control.”

Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (BVD), Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR), Leptospirosis, and Johne’s disease are the four main diseases affecting fertility. “They can be disastrous to fertility and therefore the productivity and profitability of your herd,” she adds.

“To ensure the lowest risk to your herd’s health status you need to buy from trusted herds that are BVD, IBR and Lepto accredited.

Johne’s disease risk is based on risk assessment, because of the difficulties around testing. It works on a risk rating of one to five; one being no animals within the herd testing positive for a minimum of three years, and five being positive cows present in the herd.

Establishing good relationships is key to building transparency and trust in the quality and health of stock. “Look for accreditation and risk assessment but also build good relationships with breeders so you are able to ask questions and get transparency – not only around disease but also breeding and cow/calf/bull management,” says Mrs Brooks.

If buying stock you can use Breedr’s trading platform to find breeders and sellers you can trust. Because farmers on Breedr are capturing data against their animals, when they are sold through the platform the data moves with them to the purchasing farm. This provides transparency and gives you access to medicine and vaccination records even before you commit to buying.

5. Managing cows/bulls effectively

Breeding stock need to be fit, fertile and healthy – nutrition alongside disease and fertility management are major components of a productive and profitable herd.

Tips for effective conception:

- No stress

- No immediate change in diet, social order/herd structure, or environment

Managing breeding stock needs to be easy and efficient as possible, says Ms Steele. “Organising them into management groups will make management easier and reduce stress for the stock.”

Consider:

- Body condition scoring

- Nutrition

- Health and vaccine protocols

- Culling

- Bull fertility checks

Body Condition Scoring (BCS) is a practical tool for managing the nutrition and fertility of breeding stock.

Target BCS for spring calving herds:

- Cow: 2.5 to 3 at service, and 2.5 to 3 at calving .

- Heifers: Need to be 65% of target mature bodyweight at service. BCS of 3 at calving.

- Bulls: 3 at breeding

“A BCS of 2.5 is the minimum score at service so that condition doesn’t affect her subsequent fertility,” says Ms Steele. “The main thing with BCS is to avoid the extremes at both ends and avoid sudden changes.”

Scoring is subjective to each person so make sure all staff undertake training and use the same person to condition score routinely to minimise variation between scorers.

For most suckler cows, one BCS unit equates to around 13% of body weight, which translates to 84kg per unit for a 650kg cow.

Nutrition

Getting pre-partum (pre-calving) and post-partum (post-calving) nutrition right is essential – but no drastic changes should be made to the diet six weeks pre- and post-calving.

Breeding stock need to be on a rising plane of nutrition and at the correct BCS, says Dr Henry. “You want them to reach their ideal BCS and maintain it, so you need to understand what they’re getting out of nutritional inputs to avoid condition loss,” he says.

Monitoring grass/ silage availability and quality means you can pre-empt and respond to challenges; for example, a drought in July will restrict grass intakes of grazing autumn calvers.

“You also need to think about trace element status of breeding stock –talk to your vet about testing to see where there may be deficiencies,” he says. “Using the right bolus at the right time can help address those concerns.”

Providing silage is good quality, autumn calving cows and heifers can be fed to BCS; if housed a mixed ration offers greater control, although inputs and costs are higher.

“The next egg is produced about two months prior to service, during the fresh calved period, and any drastic changes to nutrition and body condition can have a knock-on effect on its viability,” explains Mrs Brooks.

“Pre-calving nutrition is very important for the resumption of oestrus but it’s also very important in the adequate production of quality colostrum and the continuing growth of heifers themselves.

“However, most foetal growth occurs in the last trimester of pregnancy so overfeeding can result in excessive calf growth and a difficult calving. So we need to be looking at making changes no later than 10-12 weeks before calving and then maintaining her body condition through nutrition six weeks pre-calving.”

Post-calving nutrition needs to support the recovery of the calved cow, her return to oestrus and lactation. Heifers have greater nutritional demands post-calving as they have the additional demands of maintaining their own growth while lactating.

And don’t forget the bull. “Make sure there is plenty of time to address any challenges like under or over condition – the latter is often the case when purchasing bulls from the sale ring.”

The bull’s pre-mating nutrition should reflect their service period nutrition to reduce the risk of body condition loss with a sudden change in diet and energy demand. Trace elements selenium, zinc and copper are important, and can be delivered via bolus.

Culling

Breeding and culling go hand-in-hand and carrying stock with poor health and fertility will raise total costs of production and reduce overall herd performance and profitability – now and well into the future. Reviewing performance can help pinpoint individuals which negatively affect overall productivity and profitability.

“The main reason to cull is infertility, which could present as extended calving intervals and returning empty,” explains Mrs Brook. “Other reasons for culling include poor health and repetitive disease incidence as well as poor condition, low calf weaning weights, problematic calving and temperament.

And while suckler cows can go on to produce calves well into age, by 5-8 years old they will have likely reached peak production and in theory will no longer be the most genetically valuable animal in the herd.

Poor mobility and lameness are the main reasons for the premature culling of bulls.

Health and vaccination

If herd health is poor or challenged then productivity falls which has economic consequences; to be best protected breeding stock need to be vaccinated – particularly against IBR, BVD, Leptospirosis and clostridial diseases.

“It’s important that animals are vaccinated at the right time – which is dependent on the vaccine,” says Mrs Brookes. “Some live vaccines can cause a temperature lift which can be detrimental to sperm production, so bulls need to have vaccines well in advance of service.

“Speak to your vet to better understand your disease risk and appropriate protocols for your farm.”

She also advises discussing effective use of anthelmintics and flukicides as well as implementing quarantine protocols for newly purchased stock or stock from another farm.

“Quarantine for two to four weeks, it will give you the time to administer anthelmintics/flukicides as well as time to observe animals for any abnormalities in health and behaviour.

“If you’ve looked at all the management factors and still can’t identify what may be causing a fertility or health challenge then it’s time to call the vet – an upcoming annual health visit is a good opportunity as well.”

Post-service analysis

Understanding which cows are pregnant and which are not will allow you to tackle inefficiencies in your herd, cutting out losses that you would otherwise incur.

The major cost of suckler herds is associated with wintering, says Dr Henry. “The fewer cows you winter and don’t have to spend money on the better. The cost varies between farms but can be £250-£450/head. Every barren cow you can avoid keeping is saving money, which could be used to keep more productive cows.”

The only way to understand how effective your service period has been is to undertake Pregnancy Diagnosis (PD) testing. To find out more read our Complete Guide to Preparing for PD.